Interruption is All You Need: Reducing LLM Hallucination through Parallel Reasoning Diversity

A couple weeks ago, I participated in the Mercor x Etched x Cognition Hackathon. The theme of the hackathon was "inference-time compute"— and this is what I worked on for 24 hours, with some added rigor, visualizations, and analysis.

You can view the original work here and the code here— my contribution is the hallucinations section for both.

Thanks to Allison Lim and Vijay Kumaravelrajan ( alphabetical order) for helping me edit this!

TL;DR: We can scale inference-time compute to gain signal for model uncertainty by injecting an interruption token, "No, but" at varying positions in a model's chain of thought. Sampling in parallel and measuring diversity of the reasoning traces allows us to then determine when a model should refuse to answer a question— that is, acknowledge it doesn't have the knowledge to accurately respond. We demonstrate improved refusal rates on questions a model would typically get wrong, while preserving accuracy on attempted questions, though there exists a minor trade-off where accuracy slightly drops as refusal rates increase. We find this work promising for LLM applications where false negatives and positives are high-risk.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Reasoning models are all the rage these days — "thinking" longer lends itself to significant improvements in domains from coding to math for LLMs. Whether extracted through reinforcement learning or supervised fine tuning of other reasoning traces, this behavior has presented itself as one of the ways to exploit the third scaling axis of LLM performance — inference-time compute (the other two being pre-training and post-training).

One thing this reasoning process cannot do, however, is acquire knowledge. No step by step process will get a model to remember something that didn't exist in its training data. Yes, it is entirely possible for a model to reason over multiple related facts to a question, retrieve the relevant information, and form a conclusion from there, or calibrate to its internal state and realize that it doesn't know the answer through a similar process. And we do see this!

Per OpenAI on their SimpleQA benchmark: We also see that o1‑mini and o1‑preview, which are designed to spend more time thinking, choose to "not attempt" questions more often than gpt-4o-mini and gpt-4o. This may be because they can use their reasoning capacity to recognize when they don't know the answer to a question, instead of hallucinating.

But the other side of these long reasoning chains is confident confabulations that occur as a model searches for, and inevitably hallucinates, justifications for an ultimately incorrect answer. For example, models may confidently state 'Wait, I remember...' before citing a total falsehood, or claim to 'search' for information in their chain of thought when they clearly don't have tool access.

Long chains of thought in the reasoning models as the primary way of vertically scaling compute means we can easily replicate and interpretably intervene in them. s1: Simple test-time scaling is a paper that demonstrates this scaling without RL through a method called "budget forcing", where they append a "Wait" token at the end of a model sequence, forcing the model to expand its inference-time compute budget — hence the name. Even before the reasoning paradigm, several works have demonstrated improvement in performance by injecting simple tokens that don't directly contribute to problem solving, like periods.

Inspired by s1, we employ a similar method to gauge model uncertainty on question-answer tasks, with the goal of increasing calibration to internal state (does the model understand that it doesn't know something?) and overall reduce hallucination by improving refusal rates, which we define as the percentage of questions a model acknowledges as being unable to answer on any given question set.

Method

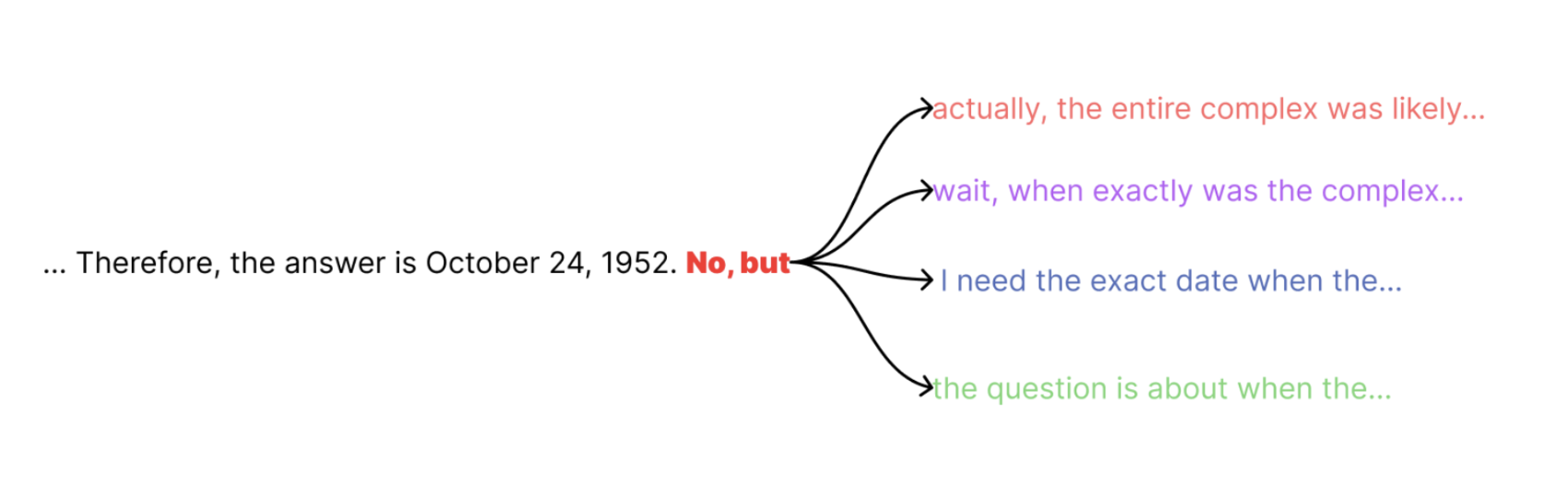

Our method implements uncertainty injection and subsequent parallel reasoning. Given an input query Q, we begin inference on our reasoning model M, allowing it to generate tokens naturally. At a predetermined position N in the sequence, we inject an interruption token – specifically "No, but" in our initial experiments - to introduce a deliberate point of uncertainty in the reasoning trace. From this injection point, we spawn P parallel continuation paths, each representing a distinct reasoning trajectory. These parallel paths continue independently until they reach their respective end-of-sequence (EOS) tokens and produce final answers. It is important to recognize that these reasoning models have a separate "reasoning" and final outputs — with the reasoning sequence prepending the final outputs, and explicitly labeled. For our experiment model, Deepseek R1, the reasoning is demarcated by <think></think> tags. So when we inject at position N, this is in the reasoning output, and the resampling doesn't see any part of the final output/answer.

To evaluate the coherence of these parallel paths, we employ a Small Language Model (SLM) to judge the diversity of the P reasoning traces. The SLM assesses how different the traces are and their coherence with one another on a scale of 1 to 10. If the diversity score exceeds our preset threshold (e.g. 6), we abstain from answering with "I don't know." Otherwise, we generate a synthesized response from the P reasoning traces using the SLM.

The intuition behind this approach is twofold. First, by introducing uncertainty and extending the reasoning process, we leverage the self-correcting properties inherent in these reasoning models. Anecdotally, models with public reasoning traces (like Claude 3.7 Sonnet and Deepseek R1) often demonstrate this behavior – they may temporarily diverge and meander off-topic but ultimately converge onto correct answers, deciding to also end their output sequence there. This suggests that if a model is confident in a fact and its reasoning, an interruption token should neither significantly affect its final answer nor its subsequent reasoning path. Second, high diversity or incoherence across reasoning traces indicates that the model is essentially gaslighting itself into arriving at some answer. If the model needs P different explanations to reach the same conclusion, we ought to question the reliability of that answer.

In more open-ended domains and for broader answers, more explanations may be better— but for fact-checking hallucination benchmarks that often have few relevant data points to latch onto during the reasoning process, our experience shows that explanation diversity typically correlates with hallucination rate. Notably, this method scales inference-time compute in two dimensions: horizontally through increasing P, and vertically through budget forcing on the reasoning model.

Experiment Details

Benchmark: SimpleQA

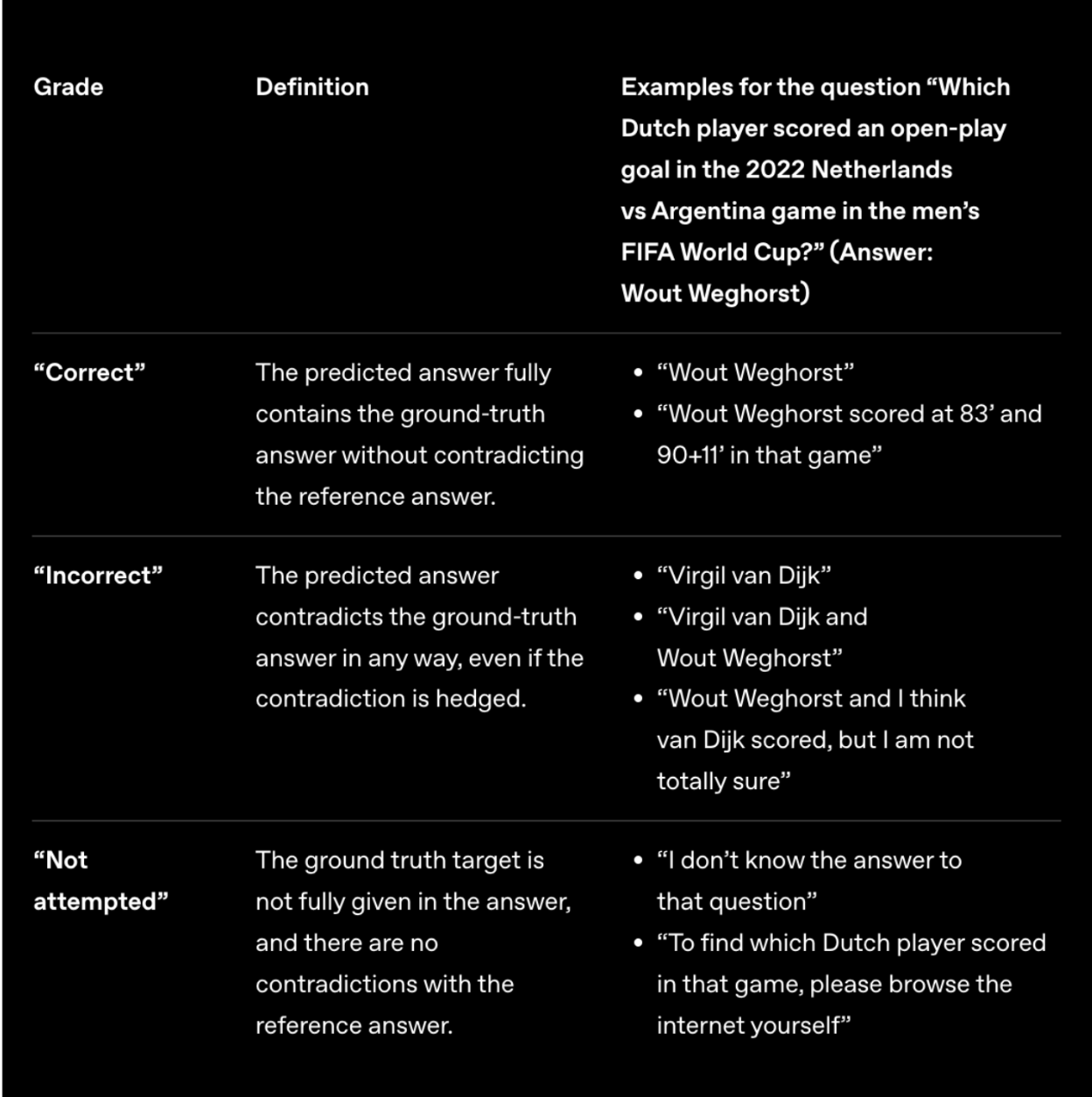

We utilize OpenAI's SimpleQA, a benchmark for measuring language model factuality, featuring 4,326 diverse fact-seeking questions with verified answers, where model responses are classified as "correct," "incorrect," or "not attempted" using a prompted classifier (GPT-4o) with a provided rubric. Given budget and compute constraints, we report results on the first 200 questions of the benchmark, instead of the full dataset.

Model

We utilize Deepseek R1 as our reasoning model, given its public reasoning traces as well as the ability to prefill and inject tokens into its thinking process (returned as a part of the messages object, surrounded by <think></think>). At the time of testing, 3.7 Sonnet did not support, through simple API, injections into the thinking tokens, and we did not get to experiment with the API for Gemini 2.0 Flash Thinking, though that potentially could've been a valid option as well.

All results for R1 are based on the full 671B version of the model, accessed through the fireworks API with a temperature of 1.0 and a top p of 1.

For our small language model, we utilize 2.0 Flash Lite. This could be replaced by any other model in theory, but we were unable to perform ablations in our provided time — and have chosen not to when reworking the results for this blog, as I don't believe SLM selection is central to the validity of our method.

One note about the use of a SLM for synthesizing reasoning traces is that it's possible the SLM will inject its own knowledge on top of the existing answers, thus compromising the integrity of our method. However, we test this by simply benchmarking the method without filtering from diversity and find it keeps the exact same amount of correct answers — demonstrating that the SLM is only responsible for synthesizing the existing answers.

Results

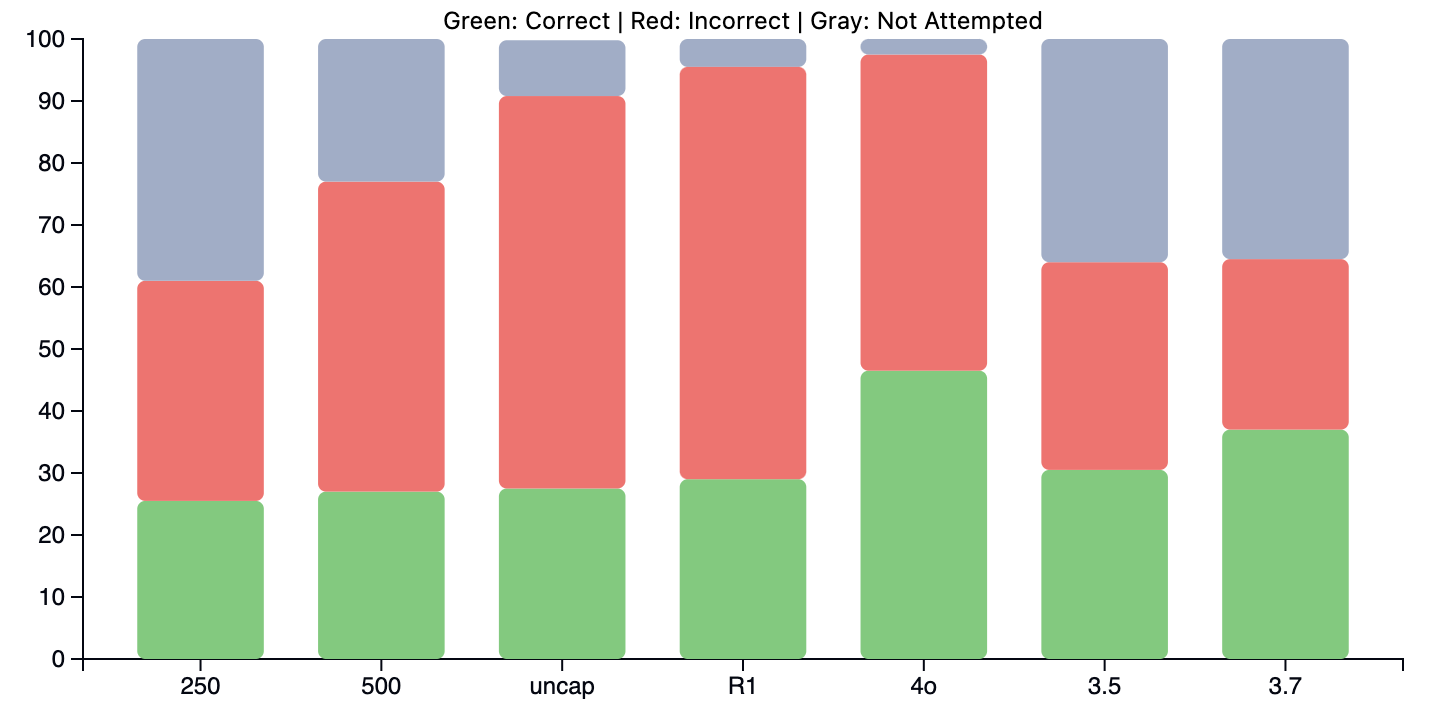

We report performance on the first 200 questions of OpenAI's SimpleQA benchmark for baselines Claude 3.5 Sonnet, Claude 3.7 Sonnet with Thinking (we were given Anthropic credits for the hackathon!), GPT-4o, and vanilla Deepseek R1. The reasoning models were provided with token caps of maximum output tokens and 10,000 tokens, respectively (though they never used anything near those limits in practice).

We also report performance on three variations of our interruption method, with N set to 250, 500, and uncapped. The first two values of N are motivated by the approximate average of ~1000 thinking tokens expended per problem we observed. We set a P of 10 and a diversity threshold of 7.

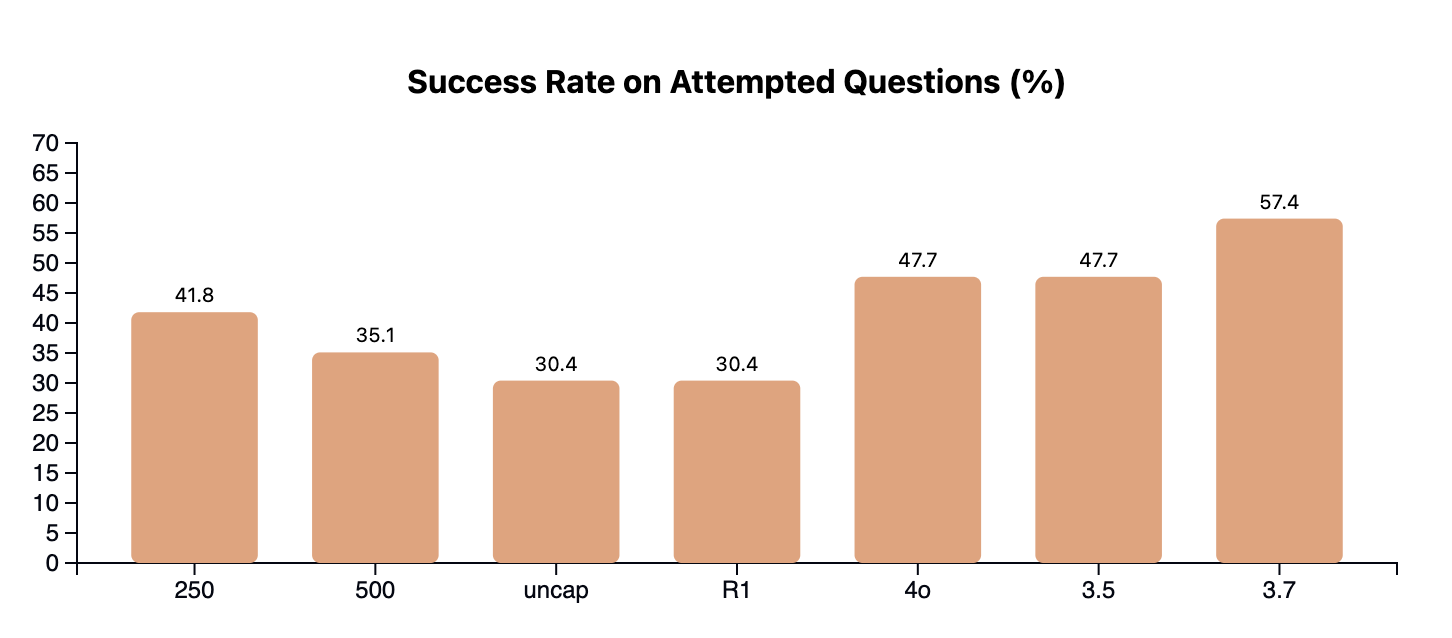

Overall, while we are unable to inject new knowledge into the model, we are able to accurately judge when a model may be wrong. We find that with interruption, we significantly decrease the amount of incorrect attempts the earlier we inject into the chain of thought, improving refusal rates by 4.5%, 18.5%, and 34.5%, respectively, to interrupt at uncapped tokens, 500 tokens, and 250 tokens. At the same time, we are able to maintain similar amounts of correct answers, with the greatest loss in accuracy (between vanilla R1 and interrupt@250) being just 3.5%.

Our accuracy on attempted questions demonstrates up to a 10% increase between vanilla R1 and interrupt@250 — with stepped performance at intermediate token positions. One explanation for these results is that the earlier we interrupt and introduce uncertainty into a token, the more likely the model is to diverge in its outputs, as less priors have been established. The comparative impact of interrupt@uncap is far less than that of interrupt@250, for example.

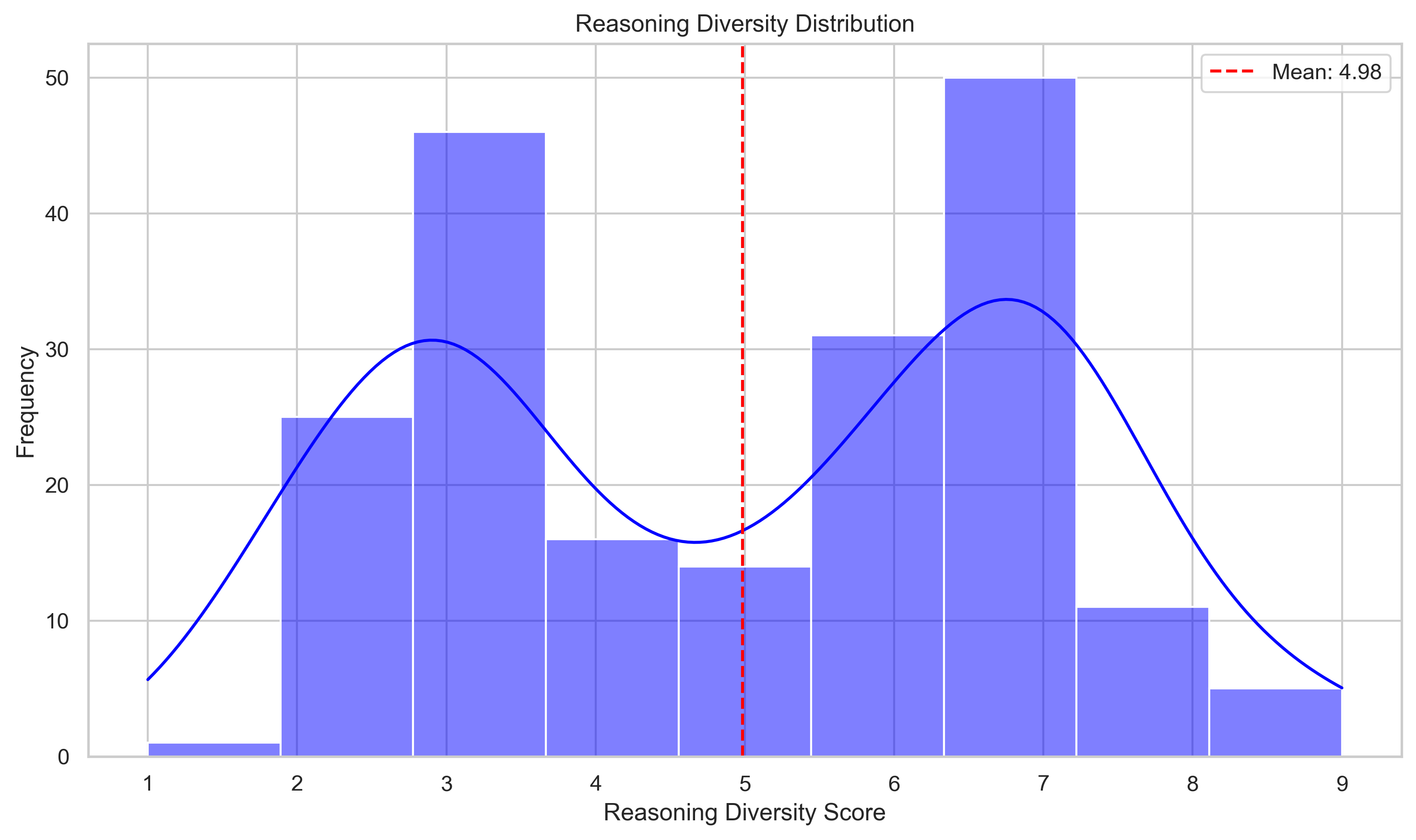

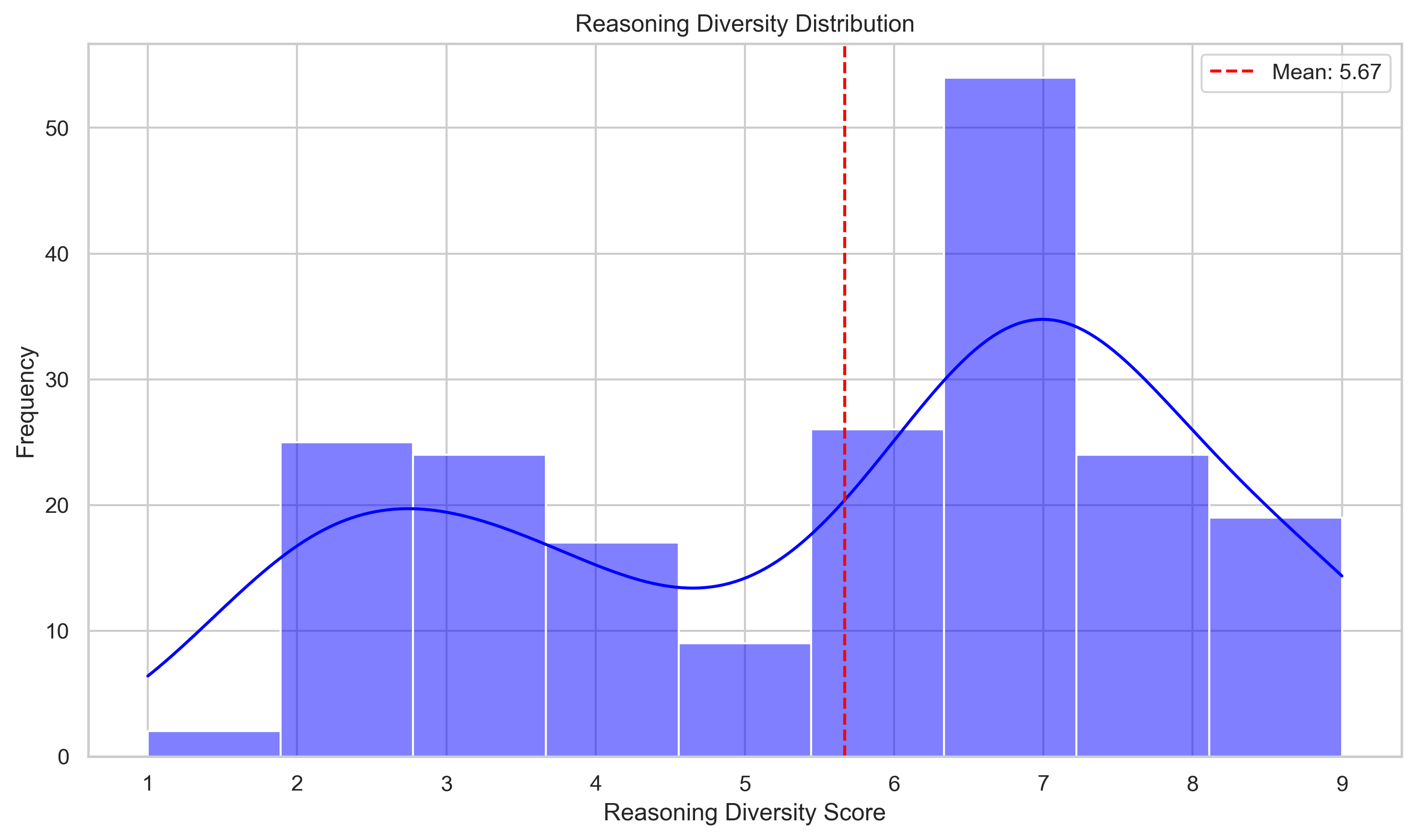

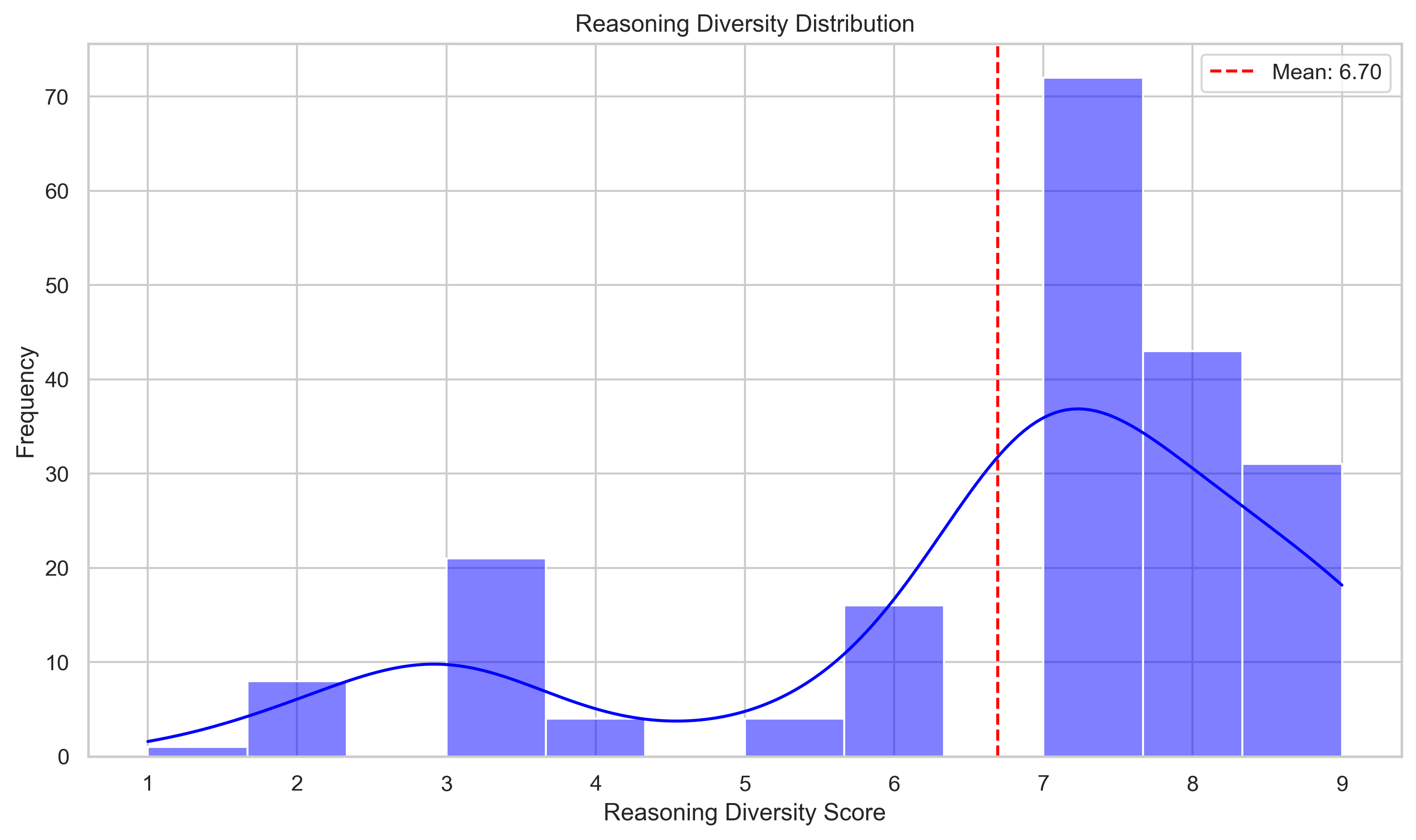

Analyzing the distributions of diversity scores for each method variation supports this as well.

We can see that for earlier and earlier interruptions, the mean diversity score across all questions increases, with a significant portion of the distribution shifting to be right of 7. You may find it surprising that even with interrupt@250, there are still some continuations with low reasoning diversity (< 5). After manually inspecting these, they all look to have similar patterns of approaches, like first checking this piece of evidence then retrieving another fact, which explains the low diversity even with an early interruption.

Some points of uncertainty

Working with LLMs is inherently stochastic and therefore messy and potentially confounding. Transparently, here are some pieces of evidence that could weaken our results, for you to form your own judgements.

One interesting point here is that while the distributions for each variation are not necessarily bimodal, there does seem to be a specific bias towards assigning scores of 3 and 7 from our SLM. This is unsurprising and likely some inherent bias in the model we chose (as well as a human bias in me, 7 was the first hyperparameter I chose to test at the hackathon). Again, I don't believe this affects the significance of the end results— but is definitely an important thing to understand when making direct comments about the nature of the diversity scores. One thing to test in future would be using text categories (not diverse, somewhat diverse, very diverse … ) instead of numbers and determining if the distribution is the same.

Additionally, in a perfect world each method gets the exact same answers correct and only changes the amount of incorrect answers it provides. This would be the clean explanation for this method. However, we also find that each variation has its own uniquely correct questions. That is, the presence of the interruption token at that specific N (250,500,uncap) results in a correct answer when the other 2 variations didn't. We see 8, 5, and 4 uniquely correct answers for methods interrupt@250, interrupt@500, and interrupt@uncap respectively. That is, interrupt@250 gets 8 questions correct that both interrupt@500 and interrupt@uncap didn't, and so on.

One potential explanation here is that earlier injection forces the model to continually decode and sample from a wider set of explanations than a later one— some of which ultimately converge back to a coherent and correct answer. After analyzing one of the questions interrupt@250 uniquely got, this makes some sense.

The question was about a comic book character and interrupt@250's continued chain of thought (from the interrupt token) focused on "discovering" more evidence (R1 often makes claims about looking something up or consulting some external source), while the other 2 methods were already mostly committed to the answer being 1 character. Interrupt@500, the midpoint between interrupt@250 and interrupt@uncap, actually veers towards the correct answer but ultimately goes back to the old wrong answer.

Of course, this is a singular example I took the time to review and unfortunately it's difficult without additional experiments to make anything more than the hand-wavey statements provided, but this is another thing to understand that exists and may affect your interpretation of our results.

Alternative Methods

Some things we tried and why they didn't work:

Another method for measuring reasoning diversity is through embeddings, by naively averaging the pairwise cosine similarity of all P reasoning traces. However, we find that these similarity scores are typically quite high and don't capture much nuance. A reasoning trace with just a single token difference, e.g. "no", may have massively different implications on the final answer while it may be very similar to another reasoning trace without that token. We also tried simply taking the consensus of the P continuations. This was actually our first attempt and experiment, but we found that many times an incorrect answer would have divergent explanations across traces, which motivated our current method.

Things we didn't try that we would love to:

- A compute-equivalent baseline that we didn't try is pass@n with accuracy measured by the consensus of the answers or simply the presence of the correct answer in the n attempts, but we haven't done this yet for budget reasons.

- Scaling up our P parallel reasoning traces and examining the scaling laws there.

- We'd like to see if directly prompting a SLM to make a decision to not attempt/keep an answer would result in the same performance

- Measuring divergence based on what variations of interruption token we use. Other options include: "Wait, but". "Actually", "Nevermind", etc.

Conclusion

Our work demonstrates that measuring diversity in parallel reasoning chains can serve as an effective signal for when reasoning models should refuse to answer questions they would otherwise hallucinate on. By injecting an interruption token ("No, but") at varying points in the reasoning process and analyzing the diversity of resulting thought patterns, we achieved up to a 34.5% improvement in refusal rates while maintaining accuracy on attempted questions within 3.5% of the baseline. This suggests that when multiple reasoning paths diverge significantly, it's a strong indicator that the model lacks the foundational knowledge to answer confidently.

The method's key advantage lies in its simplicity— it requires no additional model training and scales inference-time compute both vertically and horizontally to enable more reliable AI systems. While we focused on Deepseek R1 and SimpleQA for our initial experiments, the approach could potentially generalize to any model with exposed reasoning traces and any hallucination benchmark.

Future work would explore adaptive injection techniques that optimize the interruption point based on question type, alternative interruption tokens beyond "No, but", and applications to other reasoning models and tasks.

By providing a practical framework for improving AI reliability through enhanced self-awareness of knowledge limitations, particularly in high-stakes applications where false information can have serious consequences, we hope this work contributes to the development of more trustworthy AI systems.

A common theme throughout this blog has been that we would love to perform more experiments but find it expensive to test on the entirety of SimpleQA or generate more baselines and ablations. If you find this work exciting or intriguing and would like to support it, know of any helpful resources, or simply have questions and comments, please reach out to me at dmbai@usc.edu or any of my socials!